It should never be illegal to beg or sleep rough on the streets, no matter where you are in the world. Unfortunately, begging and vagrancy are still criminal offences in many countries, including in parts of the UK. An archaic law, the Vagrancy Act 1824, criminalises begging and sleeping rough in England and Wales.

We believe it is time for change. For this reason, CSC is standing with Crisis and other leading homelessness organisations in the UK to call for the Vagrancy Act to be scrapped.

What is the Vagrancy Act?

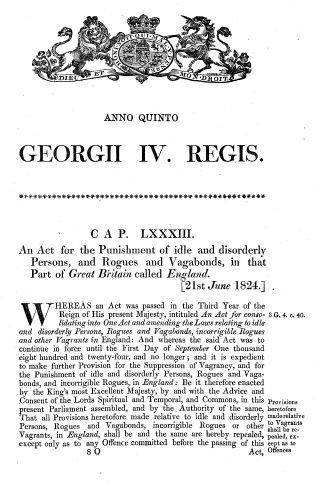

The Vagrancy Act 1824 is a law that makes it illegal to beg or ‘sleep rough’ on the streets.[1] Although the law is a product of the 19th Century— individuals in breach of the law “shall be deemed a rogue and vagabond”— it is still being applied on the streets of England and Wales today. Instead of tackling the root causes of homelessness, it punishes people who are already struggling. Worse still, it can prevent people from reaching out for the support services they need to get off the streets.

People are treated as criminals under the Vagrancy Act, even when they are not disturbing or harming anybody.[2] A new report published by Crisis, a leading UK homelessness charity, highlights that there have been over 9,000 prosecutions under the Vagrancy Act in the last 5 years, most commonly for begging.[3] However, the reach of the Act extends beyond the courts: informal enforcement of the Act means that people are moved on from places where they are sitting or sleeping rough without being cautioned or arrested. Crisis’ report quotes Pudsey, from Blackpool, on his experience:

“I’ve now had thirteen charges under the Vagrancy Act, and I’ve also been taken to court twice for it. … Half the homeless in town have been given Vagrancy Act papers now, and most of them have been fined about £100 and then given a banning order from the town centre. … Luckily, I met a local charity outreach team last October, [who] supported me into a shared flat with our own tenancy and everything. … If I didn’t have this support around me now, I’d probably be dead. People need help and housing, not being called a criminal.”[4]

On top of this, law can have a stigmatising effect. Labelling people as criminals simply for being on the streets encourages discrimination and hostility towards them by members of the public and, in some cases, by local law enforcement. It hurts people’s self-esteem and harms mental health. Instead of encouraging them to seek support, it has an isolating effect and damages trust within communities.

How does this relate to children and young people? Are there street children in the UK?

Currently, thousands of people in the UK sleep rough every night;[5] many young people choose to sleep on friends’ sofas, stay in hostels, squats or B&Bs rather than telling their families or the local authorities that they need help.[6] What’s more, the number of children living in poverty stands at 4.1 million and is rising.[7] This means that more young people are at risk of becoming homeless and spending time on the streets.[8]

Although homeless young people should be eligible for housing and support under the Children’s Act 1989, lawyers and charities have warned that many are wrongfully refused support, and that local councils are struggling to meet their legal duties in a climate of strict budgetary constraints.[9] What’s more, the age of criminal responsibility in England (the age from which you can be charged and prosecuted for criminal activity) is 10, the lowest in Europe.[10] This low age of criminal responsibility means that children and young people who beg or sleep rough on the streets can be moved on or arrested under the Vagrancy Act.

This puts the UK’s most vulnerable young people at greater risk. That’s why we believe the law urgently needs to change.

The Vagrancy Act does not belong in modern Britain.

Both Scotland and Northern Ireland have repealed the Vagrancy Act, but it is still in force in England and Wales. There have long been calls for the Act to be scrapped, ranging from petitions with tens of thousands of signatures[11] to civil society campaigns, but attempts to repeal the law have been blocked and delayed.[12]

When questioned in Parliament about the Vagrancy Act, the UK Government said:

“We must ensure that people get early support to prevent them from ever becoming homeless, and we must provide support on a broader basis than ever before to help people off the streets. … [T]he Government are clear that no one should be criminalised in this country for having nowhere to sleep. That is quite wrong, and we are determined to tackle it.”[13]

Despite this positive statement, the Government has not yet committed to repealing the law. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government has promised a review into the wider framework of laws and policies on homelessness, including the Vagrancy Act. The Government’s reason for not repealing the Act outright is that some still view its enforcement as a last resort method to encourage homeless people off the street and into shelters.[14] Yet threatening or criminalising homeless people using the law achieves the very opposite of this, pushing them “further into poverty and social exclusion, from which they cannot escape.”[15]

At Consortium for Street Children, we believe the time for repeal of this outdated law is now.

This is the UK’s chance to be a model example for other States.

Laws on begging, vagrancy and loitering exist all over the world, as our Legal Atlas for Street Children demonstrates. Many of these laws are based on the Vagrancy Act. However, there is a growing international consensus that laws that make it illegal for people to beg, sleep rough and spend time on the streets are harmful and ineffective:

- The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child explicitly called on governments to decriminalise status offences in its authoritative guidance on street children, describing the criminalisation of begging and vagrancy as direct discrimination.[16]

- Leading international experts on adequate housing and the sale and sexual exploitation of children urged for the repeal of these laws to prevent children from being abused and criminalised.[17]

- The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights criticised laws that penalise begging and homelessness as creating obstacles to the elimination of poverty.[18]

- The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights condemned vagrancy and begging laws for reinforcing discriminatory attitudes towards people on the streets.[19]

Repealing the Vagrancy Act would be a step towards a real commitment to equality, setting a positive example for States all over the world.

How to support the campaign to scrap the Vagrancy Act

There are several ways that you can lend your support to the campaign to consign this law to the history books.

- Write to your MP: If you are a UK resident, let your local MP know about this law and tell them why they should support repeal. You can find out who your MP is here.

- Share the campaign on social media: Raise awareness by sharing this post and the report by Crisis on your social media channels. You can often tag your MP on Twitter and Facebook if you want to quickly draw their attention to a post.

- Donate to us to help support our advocacy work: We work with our international network all over the world to defend the rights of street children. Consider sponsoring our efforts by making a one-off or regular donation here.

[1] Begging is illegal under section 3 of the Vagrancy Act 1824, and sleeping rough is illegal under section 4.

[2] Crisis report, ibid, pages 10-20.

[3] Crisis, ‘Scrap the Act: The case for repealing the Vagrancy Act (1824)’, 2019, available online here. Statistics on prosecutions under the Vagrancy Act can be found on pages 12 to 16.

[4] Crisis report, ibid, page 23.

[5] Homeless Link, ‘Rough sleeping – our analysis’ (figures published for 2018), available online here.

[6] Crisis, ‘Hidden Homelessness: Britain’s Invisible City’, 2004, page 5.

[7] Consortium for Street Children, ‘Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights ahead of country visit to the United Kingdom’, 2018, available online here. Statistics on child poverty and youth homelessness in the UK can be found on page 1.

[8] CSC submission, ibid, pages 1-2.

[9] May Bulman, ‘Vulnerable children forced into homelessness as local authorities routinely ignore child protection laws’, The Independent, 05 March 2018, available here.

[10] Houses of Parliament Postnote Publications, ‘Age of Criminal Responsibility’ (June 2018, Postnote No. 577) available here.

[11] UK Government and Parliament Petitions, ‘Repeal the Vagrancy Act 1824’, available here.

[12] House of Commons debate on the Vagrancy Act 1924, raised by Layla Moran (Liberal Democrats) on 29 January 2019. Quote by Layla Moran MP at c797.

[13] House of Commons debate on the Vagrancy Act 1924, raised by Layla Moran (Liberal Democrats) on 29 January 2019. Quote by Jake Berry MP at c797.

[14] House of Commons debate on the Vagrancy Act 1924, raised by Layla Moran (Liberal Democrats) on 29 January 2019. Quote by Layla Moran MP at c794.

[15] Housing Rights Watch, ‘Mean Streets: A Report on the Criminalisation of Homelessness in Europe’, 2013, page 11, available online here.

[16] UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No.21 on children in street situations, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/21, 21 June 2017, para. 26, available online here.

[17] Joint statement by the Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography and the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, ‘They are not disposable – UN experts remind States that street children have rights too’, 12 April 2015, available here.

[18] Foreword by Nils Muižnieks in FEANTSA et al, ‘Mean Streets: A report on the criminalisation of homelessness in Europe’, September 2013, p. 9-10, available online here.

[19] Principles on the Decriminalisation of Petty Offences in Africa, available here.